Reports from the field

PhD Days – Reports

PhD Day 2021 - 'Reviewing Reviews': A report by Sofia Baliño

For many doctoral students and post-doctoral researchers, entering the world of academic publishing can be an exciting prospect – and a daunting one.

The 2021 PhD Day set out to help demystify that world. Organized by Aleida Auld (UNIGE) and Patrizia Zanella (UNIGE), the sessions gave a rich and thoughtful overview of academic publishing in the humanities – from outlining introductory concepts about peer review to sharing best practices for preparing our work for publication.

The four-hour event was held on Saturday May 8 on the Zoom platform, bringing together PhD students, postdoctoral researchers, and professors for a morning of presentations and break-out room discussions. It was a valuable opportunity to talk openly about the experiences we have had to date in publishing our work, our questions and concerns about the process, and the aspirations we hold. The PhD Day also gave us the chance to meet new colleagues and engage with our existing ones – an opportunity that I valued all the more this year given the continued challenges wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has made forming and nurturing these relationships harder.

The first presentation was devoted to the subject of peer review. Emma Depledge (Assistant Professor of English Literature, UNINE) explained what peer review is and how it works, what the process looks like for publishing in journals, and sample questions that reviewers are often asked to consider. She gave valuable guidance on how to respond to peer review, especially in those cases where a prospective author is asked to “revise and resubmit,” and what lessons we should keep in mind as prospective reviewers ourselves.

The second presentation was by Ursula Kluwick (Senior Researcher SNF, Modern English Literature, UNIBE), who built on these key principles and showed their application in the context of essay collections. Along with setting out what these essay collections might entail – and what that means when it comes to the use of peer review – she provided a detailed overview of the benefits and drawbacks involved in different types of collections. Her analysis of the peer review process from the editor’s perspective showed how peer review plays an important role in informing the editorial process and complementing an editor’s expertise.

The third presentation was by Bryn Skibo-Birney (Postdoctoral Researcher, American Literature, UNIGE), who brought an insider’s perspective from her experience editing book reviews at Transmotion, a peer-reviewed academic journal devoted to Indigenous studies. Among the important insights and tips that she shared was the value of having an academic website, personal website, or both to ensure that editors can easily find us online and learn about our work. She walked us through the outreach process for pitching to book reviews editors, along with the importance of being familiar with a journal’s archive and style when submitting pitches and full reviews.

These three presentations set the stage for an in-depth exchange during our next session, where we were able to apply some of these principles and insights into practice. During Session 2, participants were split into “break-out rooms,” which gave us the chance to learn more about each other’s work, publishing experiences, and interests. We also got the chance to see what book review feedback looked like and how to engage with it effectively, with guidance from the presenters.

For the third and final session of the day, Emily Hockley, Commissioning Editor at Cambridge University Press (CUP), gave us the publisher’s perspective on academic writing in the humanities. One of the most important takeaways from her presentation is that while monographs may be inspired by our doctoral dissertations, they also need to be much broader in their coverage and approach. She explained how to submit a proposal for a monograph, how to adapt a PhD thesis for publication, and how to distinguish between what material is best suited for a journal and what might make for a strong monograph proposal.

The business aspect of academic publishing was another core component of her presentation. Understanding a publisher’s target markets and audiences is vital, she told us. The length of our monographs also affects production costs, which is another factor to consider. Securing the permissions to include any images in advance can also make the process far easier. She then walked us through what the CUP review procedure is normally like, along with what other routes to publication are available.

Across the day’s sessions, certain common threads came together. Among these were the importance of doing our homework, whether it means researching a publisher’s target audience and lists or examining how a journal approaches its book reviews. Another thread that ran through the presentations was that peer review is not meant to be scary: it is meant to strengthen our work and that of the editors we collaborate with, and we should also keep that in mind if we someday become reviewers ourselves. Lastly, the presenters showed us that there are several different venues for publishing our work, which gives us a wealth of options to choose from – while also requiring that we understand the benefits and drawbacks of each option depending on what we wish to achieve.

As the PhD Day drew to a close, I was deeply impressed with how much valuable material we had learned in the space of just four hours, thanks to the extensive efforts of our organizers and panelists. As a result, the world of academic publishing now feels far more approachable than it had previously. The benefits go well beyond that, however. The PhD Day provided a reassuring reminder that we have a large community of researchers and publishing professionals to guide and support us as we chart our paths in life.

Lausanne, 1 December 2018: PhD Day: Co-Supervision and online-presence for careers in and beyond academia - A report by Anne-Claire Michoux, University of Neuchâtel

This year’s PhD Day, co-organised by Prof. Emma Depledge, Cécile Heim, and Patrizia Zanella, held in Lausanne on the 1st December was, as always, a wonderful opportunity for doctoral students from both literature and linguistics to meet and share their experience. We were warmly welcomed with fresh croissants and a multi-lingual coffee machine that required all our skills as doctoral candidates and challenged our ability to work in a team. The event this year addressed the use of social media as career building tools and the, sometimes, more delicate matter of supervision and co-supervision. We were extremely fortunate to have the wonderful Dr Mary Flannery as our guest speaker, who led the discussions in a constructive and supportive way, with enthusiasm and humour, which, for those of us reaching the end of our PhDs, as for those in the early phase of the doctorate, was hugely helpful in terms of demystifying the beast that the thesis can be.

Mary is a very generous scholar and a talented teacher whose energy is contagious. As someone who is a little allergic to social media, I had always approached the issue with a certain amount of dread and scepticism, but Mary reminded us that it allows us to be in control of our career; rather than leaving one feeling overwhelmed, finding the right platform can be hugely empowering. After sharing how we each use social media (or don’t) for research purposes, Mary presented us with lots of tools and practical tips for managing our online presence, which is something we all need to consider, without ever being dogmatic about it. She encouraged us to be creative and showed us various ways in which academics had combined their scholarly interests with their other interests and even turned their social media presence into a career. How to go about social media was an important part of the discussion. The point wasn’t that we all set up a twitter account or start a blog on the spot, but to think about how social media could work for us, while always considering the drawbacks. If we use Facebook for both private and professional contacts, how do we negotiate this? How do we go about setting a personal webpage? How much time should we spend on this? We covered the different social media platforms we can use as academics, as well as those platforms that combine our personal interests with our identities as researchers. These include institutional pages and formal platforms such as academia.edu and researchgate, personal webpages and blogs, as well as twitter, Facebook, or even instagram. We also considered the ways in which we can use them in our own teaching. The point was to explore the different avenues open to us and reflect on what is the right fit for us. I personally left the workshop feeling more empowered and more open to seeing social media as a career building tool.

A very helpful part of the workshop was Mary’s suggestion that we brainstorm the skills and interests we have, those we had before starting our PhDs and those we gained during our research, all of which we can capitalise on for academic as well as non-academic careers. Mary reminded us that we were people before we ‘became’ PhDs, a very healthy reminder. Social media is actually a great way of combining our personal interests and our areas of expertise. ‘Runners get tenure’ so never underestimate the difference your secret hobby can make.

The afternoon session was a group discussion on the pros and cons of co-supervision, as well as the different ways of managing our relationships with our supervisors. Figuring out what works for us is important, as is communication. Your supervisor is not your friend but it is a particular kind of relationship that is not a traditional boss/employee one. We discussed the benefits of drawing up a contract at the beginning of the PhD, revising the contract if necessary, and having yearly meetings to review the state of our research and how our career is progressing. An important point was to also seek help and support from our peers, at different stages of their careers.

The day was wrapped up in a spirit of conviviality and generosity with an informal apéro that rounded a successful and enjoyable PhD day.

Lausanne, 1 December 2017: PhD Day: Writing and Job Interviews – a report by Kader Hegedüs and Hazel Blair, University of Lausanne

Organised by Prof Agnieszka Soltysik-Monnet and Dr Joanne Chassot at the University of Lausanne, this workshop focused on two processes inevitably generating apprehensions for doctoral candidates: being interviewed for an academic job, and writing. It is no wonder that the workshop was particularly successful, gathering about twenty doctoral students at different stages in their research from the Universities of Lausanne, Geneva, Neuchâtel, Fribourg and Bern.

Our brains and bodies fuelled by coffee, tea, juice and pastry generously provided by CUSO, we started the day with a discussion led by our two invited speakers, Professors Anita Auer (UNIL-Linguistics) and Will Kaufmann (U. of C. Lancashire). Articulating their talks around, respectively, Swiss and UK institutions, Anita and Will introduced us to the overall process of applying and being interviewed for early career academic positions. This comparative structure allowed us to understand some of the institutional and cultural differences between the two countries, in particular their respective attitude towards the thin line between self- and over-confidence, as well as the divulgation of personal information – for example with regard to negotiating family-life and professional mobility. These distinctions were naturally complemented by numerous and fruitful intersections between the two discussions. Both speakers have invited us to brainstorm on what to include or dismiss in our CV, to adapt our application to each posting, as well as to present the right balance between teaching, research and administrative experience in order to correspond to the desired profile. Underlying this process was, they reminded us, an essential but too-easily forgotten prerequisite: to be thoroughly informed about the institution we apply to, and to know exactly where we can fit, how we can contribute, and with whom we can collaborate in the departments we seek to join.

After a short break, the morning session was concluded in the most concrete of ways with a succession of mock interviews conducted by Anita, Will and Agnieszka. Three courageous volunteers, Aleida Auld (UNIGE), Camille Marshall (UNIL) and Hannah Hedegard (UNIBE) were thus interviewed in relation to their respective fields, namely Early Modern English Literature, Medieval English, and Linguistics. Stressing the heterogeneity of hiring committees in terms of expertise, expectations and personalities, the interviewing panel pushed the candidates to demonstrate their ability to make their qualities as explicit, accessible, and compelling as possible. With questions ranging from the candidates’ teaching philosophy, and the summary of their research project, to issues of public outreach, this exercise provided a rich sample of what can be expected during such interviews. Some of the brilliant answers provided by Aleida, Camille and Hannah were in this regard very inspiring, inviting us to reflect on our ability to assess our own needs, strengths, and weaknesses. Incidentally, these same considerations were also about to frame our afternoon discussion on writing.

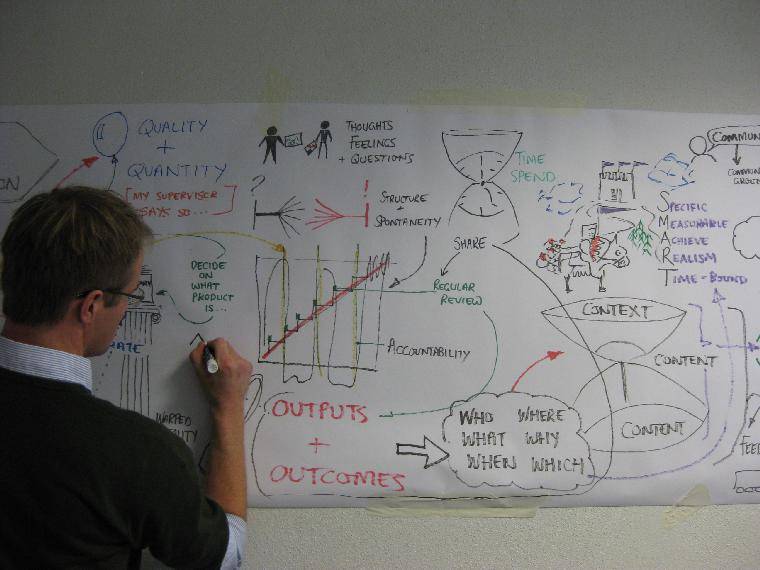

After lunch at UNIL’s Restaurant de Dorigny, we returned to the classroom for a discussion on how to write mindfully, led by Joanne Chassot. Joanne encouraged us to be honest about our writing habits so that we might identify strategies for improvement, offering some suggestions from her own experience and that of others. She asked us to consider the benefits of writing mindfully, using ‘mindfulness techniques’ such as meditation, breathing exercises, and observation before and during the writing process.

We also discussed out current habits as a group. One of the most enlightening things about this session was hearing about the different ways that people approach the writing process. While some people said they preferred to write continuously over longer periods, others expressed a preference for writing in short chunks, using variations of the Pomodoro Technique. We discussed the benefits and limitations of these habits and preferences, but what became most clear was that there is no ‘one size fits all’ solution when it comes to writing or tackling writer’s block – we all have our own styles and methods that we have been fine-tuning since our undergraduate years.

Nevertheless, simply using a tried and tested method does not mean there is no room for improvement, and Joanne encouraged us to always be mindful of our practices, to acknowledge problems where they exist, and to remain open to experimenting with possible solutions, such as keeping a logbook, freewriting, writing longhand, or using online tools such as BlindWrite to overcome hurdles in the writing process.

While acknowledging the differences in our writing methods, our group also bonded over some of our quirkier writing rituals, such as always needing to have a cup of tea to begin writing, feeling a desire to start at a particular time, or wanting to have done the dishes before starting. The honesty displayed by attendees in this area led to interesting reflections on identifying the thin line between preparation and procrastination, and useful insights into the various ways one might choose to integrate writing into one’s daily routine.

Overall, the day provided a useful forum for doctoral researchers at all stages of their careers to meet and discuss their shared challenges as junior scholars during and beyond the thesis.

Neuchâtel, 11 March 2017: PhD Day: Conferences and Publication – a report by Anne-Claire Michoux, University of Neuchâtel

This one-day workshop was one of the most relevant CUSO workshops I have attended so far and I would strongly recommend CUSO keep running these sessions annually as they are an invaluable opportunity for starting and ongoing PhD students to discuss seemingly simple yet essential elements of an academic career. As PhD candidates we are asked to give priority to our thesis, and it was indeed mentioned that “A good PhD is a finished PhD”, but we were also reminded of the other ‘boxes’ that need to be ticked during the course of a doctoral programme if we want to pursue a career in academia, namely conference attendance and participation and publications, both during the PhD and transforming the thesis into a monograph. The conveners and the speakers focused on the idea of balance, of finding ways to conciliate the different aspects of an academic career, to ensure that we would then stand in good stead for future applications. The event was truly geared towards current doctoral candidates. Speaking to other participants after the event (we were a mix of literature and linguistics students), we all agreed that we had greatly benefited from this event, which, though daunting at times, was a necessary and constructive seminar. Some participants were finishing MA students and they found it extremely helpful as well. Some of the tips are applicable to our future professional lives.

The day was divided between conference attendance and publications. We discussed why attend conferences (keeping up with current research, building a network, trialling out ideas and getting feedback, etc.), how many to attend and where, how to write an abstract (a particularly helpful exercise), how to write the dreaded ‘bio blurb’, how to best use powerpoint and other materials, and how to manage nerves. Dr Depledge advised us that conferences should “work for us” – while they are an important aspect of an academic career, they should be part of our doctoral research and should be chosen according to our research interests. We also addressed the issue of funding, where to apply for funding, and how to write a successful application. We then discussed publications, how many we should aim to submit, and what we should consider when submitting our work (how to find which journals are the best fit, what to expect once we submit an article). The final topic was how to transform the thesis into a monograph. Points like how much of thesis has already been published elsewhere were mentioned, which is not something that we necessarily think of during the course of our PhDs. Although few of us are currently at this stage in our career, it was still incredibly helpful to find out what aspects to consider when approaching publishers. It was an important reminder that, whilst research is our main focus, we should be thinking about our long-term professional goals.

One point I wish to stress was the genuinely supportive and encouraging atmosphere of the workshop. Dr Perry early on reminded us that one important aspect of an academic career is generosity, and the workshop was conducted in that spirit. Drs Depledge and Leonard very kindly circulated monograph proposals they submitted to academic presses, which was incredibly generous of them, especially when other academics are so reluctant to share thoughts or experiences. All speakers were incredibly friendly, welcomed any questions we had, and were very honest about their own experiences. We all left feeling that we are part of a community and with a few more tools to tackle our academic future.

Neuchâtel, 28 November 2015: CUSO Workshop on Tools for Digital Humanities: A Practical Workshop – A Report by Tobias Leonhardt, University of Bern

The goal formulated by Prof Elena Pierazzo (Université Stendhal Grenoble III) at the outset of this workshop sounded rather improbable at first: To teach the basics of XML in, and here I quote, “five minutes”. Sure enough, however, it is well within this time frame that she shows us a slide that says, in big letters, “That’s all folks. You have learned XML!”, we start to code away, and soon even succeed in computing some cooking recipes.

XML is an exciting language that was new to most of the workshop participants, but Prof Elena Pierazzo enabled us to see and learn a lot about it in only one day. She showed how a myriad of tasks that we do in our every-day lives are possible only because somewhere in the process XML is spoken: not only is this true for many computer programs we use on a regular basis such as Word, but also for cash transactions or refuelling a car. Besides enhancing our consumer vision, we adopted the developer perspective, learned about mark-ups, elements, attributes, syntax, et cetera, and thus acquired the skills to work with XML ourselves. The software we used is called Oxygen, which is, due to its nicely structured interface and its functionality, ideal for learners and experts alike. The tasks soon became more difficult, and instead of cooking recipes, old manuscripts had to be transcribed. How to treat main text and annotations, indentions and page breaks, deletions and missing or illegible parts? In trying to answer these questions, it became apparent what XML is capable of, how seemingly simple things require careful and very much conscious planning and coding, how the basics may indeed be conveyed in five minutes but that, like so often, mastery requires a lot of practice. These exercises and the insights they provided are transferable so that all participants, and not only those focusing on manuscripts in their academic career, have profited from the workshop. Tackling LaTeX or Macros, for instance, does not seem to be impossible anymore.

On behalf of all the participants, I wish to thank Prof Elena Pierazzo for equipping us with this XML toolkit (and cooking recipes), and Erzsi Kukorelly (University of Geneva), Lucy Perry (University of Lausanne) and Patrick Vincent (University of Neuchatel) for the organization of this workshop. It was enjoyable and fruitful to delve into a new topic, to interact with others during coffee and lunch breaks, or even to go on a short walk at Lake Neuchatel in the autumn sun.

Neuchâtel, 6 December 2014: CUSO PhD Day – A Report by Aleida Auld-Demartin, University of Geneva

How might job and funding applications differ? How much of a potential future monograph should you try to publish while writing the thesis? What do Swiss organizations in particular look for when funding research projects? What are the advantages and disadvantages of co-supervision? And what should you not do in a job interview? These are just a handful of the questions that were addressed at the most recent CUSO PhD Day which took place on December 6, 2014 at the University of Neuchâtel. In attendance were 19 doctoral students of English literature and linguistics from the universities of Geneva, Fribourg, Lausanne, Berne, and Neuchâtel.

The workshop was divided into two sessions, each with its own panel. In the morning, the experience of writing a PhD was discussed by six recent graduates: doctors Joanne Chassot (UNIL), Emma Depledge (UNIGE/FR), Markus Iseli (UNINE), Rahel Orgis (UNINE), and Juliette Vuille (UNIL).

The afternoon session focused on searching for jobs and applying for funding. A number of workshop participants had responded to mock job advertisements by contributing cover letters and CVs. After reviewing these documents in small groups, the participants reconvened for the panel discussion. Lending their expertise were literature and linguistics professors Margaret Tudeau-Clayton (UNINE), David Britain (UNIBE), and Martin Hilpert (UNINE), along with doctors Mary Flannery (UNIL) and Emma Depledge (UNIFR).

One of the great strengths of the workshop was its ability to offer practical information and tools to a diverse group of students. I asked three of my colleagues, each of whom are at different places in their degrees and work on distinct periods, what they took away. Kilian Schindler (1st year UNIFR), who responded to the mock advertisement, said he appreciated discussing “concrete examples of CVs and cover letters with other people,” which gave him an idea of “how they might be perceived from different perspectives,” including those of professors and PhD students. Bryn Skibo-Birney (2nd year UNIGE), who also responded to the ad, said the feedback on her CV and cover letter made her “feel more confident in representing [her]self and [her] work to outside parties.” Finally Sangam Macduff (4th year UNIGE) found “the practical advice on applying for jobs extremely useful.”

Like Kilian, I am in the first year of my doctorate in early modern literature. From the PhD day I retained various suggestions, such as highlighting mobility in applications for Swiss funding, and networking with other doctoral students prior to a conference so that there are some “familiar faces” at the event itself. I also realized how important it is to find and develop my own voice in any application.

In closing and on behalf of the participants, I wish to thank Dr. Emma Depledge (UNIFR) and Professor Margaret Tudeau-Clayton (UNINE) for organizing such an enjoyable and useful workshop, and the panel members for giving their time and sharing their experience.

Geneva, April 5, 2014: PhD Skills Day - A report by Amy Brown, University of Geneva

On the 5th of April an intrepid band – mostly doctoral students, with a scattering of guest MA students to liven the mix – gathered in a computer lab at UniGe. Undeterred by mysterious technical hitches, we set ourselves up for a day of skills-acquisition. One of the day’s biggest strengths was that all four speakers worked methodically through their material, making each step clear – which is excellent, but makes for a very short report. In brief, then;

We began with research skills:

· Hélène Vincent, English librarian extraordinaire, gave us an overview of different kinds of electronic research tools (databases, journal hosting, bibliographies, and so on) and walked us through selected tools for literary research.

· Sam McDuff, chief Zotero fan for the department, demonstrated his own use of the bibliography-building and note-storing tool, including pulling citation data from online resources and integrating Zotero with your word processor of choice. For those with laptops, Sam spent some time helping set up and troubleshoot Zotero installation, and we all went home with a handy set of instructions for optimising Zotero on home and work computers.

Moving on to writing and drafting skills:

· Prof. Deborah Madsen spent some time pulling apart and critiquing the structure of an article in her field, with particular emphasis on topic sentences and transitions between sections of argument. Having identified the structural strengths and weaknesses in this text, we talked about ways the structure could be improved to better convey the argument, and Deborah suggested strategies for improving our chances of seeing those weaknesses and opportunities in our own work. She highlighted ‘Reverse Outlining’ as a way of figuring out what one has written in order to figure out how to get to what one wants to have written.

· Nicholas Weeks sat us down with Microsoft Word and talked us through the process of building custom templates and styles to reduce the work of thesis-formatting. He also demonstrated the use of image-to-text scanning technology to facilitate keyword searching a scanned archive of research material (which one might store in Zotero, as it happens!).

The day was long – and broken up by a longer-than-usual (but delicious) lunch – but extremely practical and informative. There was definitely more to be said, or practiced, for each skillset, and I at least will definitely sign up for further workshops in this vein when I get the chance.

Rapport du Workshop sur le Post-féminisme avec prof. Angela McRobbie (Goldsmiths) et prof. Rosalind Gill (City University London) - Par Isis Giraldo, Université de Lausanne

Le workshop sur le post-féminisme organisé avec le soutien de la CUSO en études genre et la CUSO en anglais a eu lieu à l’Université de Lausanne le 20 et 21 mars 2014. Pour l’évènement deux figures importantes dans les cultural studies britanniques travaillant sur le post-féminisme ont été invitées en tant que guest speakers et discutantes.

Les conférences, ouvertes au publique, ont eu lieu le matin. Pendant l’après-midi les doctorant.e.s inscrit.e.s pour la présentation ont présenté leur travail devant les participants et les intervenantes invitées. Chaque doctorant.e a eu 30 minutes pour sa présentation suivi d’une discussion. Nous avons eu six présentations au total, trois lors de chaque après-midi. Le jeudi, tant McRobbie que Gill ont offert des commentaires constructifs aux participant.e.s. Le vendredi, McRobbie ayant du partir, la tâche a été entièrement assumée par Gill.

Le retour des tous/toutes les participant.e.s a été très positif. Ils/elles ont trouvé que la qualité des interventions des invitées a été excellente et que le retour s’est fait de manière affable mais professionnelle. De manière générale les participant.e.s ont trouvé que la relation qualité et informalité a été bonne. Finalement, l’internationalité des deux intervenantes a été signalée comme l’un des points le plus fort du workshop.

McRobbie comme Gill ont trouvé l’atmosphère agréable, se sont montrées enthousiastes, et ont apprécié la variété des projets des doctorant.e.s.

Geneva, November 25-16, 2013: The Media of Literature in the Digital Age - A report by Amy Brown, University of Geneva

The CUSO workshop on ‘The Media of Literature in the Digital Age’ began on Friday with the big questions – what are the Digital Humanities, and what are they for? – and ended on Saturday afternoon with practical warnings to never trust a magnetic storage device to preserve your data. Over the course of the weekend, it seemed to me that there were two conceptual threads running through the various workshops and papers: on the one hand, digital media as efficiency tools, to help us do more efficiently or more collaboratively that which our discipline already does; and on the other, digital media providing opportunities to engage with and experience our source texts quite differently. The third concept which arose again and again was that of the communication divide between humanities and technology specialists, and I will comment briefly on that before moving on to the conceptual issues.

The conference was opened by the Dean of Letters, Nicholas Zufferey, who began by announcing that he did not know what the digital humanities were. Digital media, he reminded us, are increasingly important in all fields – the humanities are not alone in that. Reflecting on the shift in English terminology from ‘Humanities Computing’ to ‘Digital Humanities’, he concluded that, whatever the digital humanities might encompass at the moment, we should strive to ensure that they remain the digital humanities, focused on the disciplinary needs and interests of the humanities first and foremost.

That sounded all well and good, until we started getting into the nitty-gritty details of describing the parameters of our texts in terms which are compatible with computers and computer programming. How many of us were discomfited by the description, in Peter Stokes’ (King’s College London) workshop on project modelling for textual databases, of a text as a ‘series of characters arranged into words, each word consisting of characters bounded by a space or punctuation’? As a medievalist, I spent my time working against the habitual assumption that a text must be interacted with in written form! In the same vein, we heard a gasp of betrayal from the Early Modernists upon being told that a line break does not constitute part of a text. Was this not a travesty against literature, reducing the text to data?

Perhaps so. However, in his lecture, Peter Stokes cautioned us against thinking of a digital edition, and especially not a digital facsimile, as ‘an online manuscript’. ‘This is not a book,’ he titled his lecture: it is a tool; an edition which is useful for some purposes and not others; a facsimile. It is not, and should not be, the same thing as a book or text. Getting that product into accessible form requires thinking carefully about which features of your text need to be represented, and which do not, as well as about how you will later use the digital product. In this respect, I experienced an unexpected case of déja vu: in a past life I once held a job which, in part, involved assisting specialist staff from various divisions to distil their IT wish-lists and turn them into concrete deliverables. Let me tell you, it is not much easier for your average government policy section to describe what they want out of a collaborative wiki than it is for a gaggle of literary scholars to describe a ‘book’ as a ‘series of images with associated plain-text rendering of the words depicted’.

The question of what ‘is’ the text was central again in Daniel Ferrer’s (ITEM Paris) talk on digital tools for genetic studies. Ferrer’s institute works not on finished texts, but on drafts, notes, and the process of writing – the ‘genesis’ of the literary work. In this field, he explained, digital editions and online facsimiles allow the scholarly – and sometimes the general – audience to engage with the author’s drafts in ways which are simply impossible in hard copy publishing. Unless one has access to all the available manuscripts, it is only with a database of images and transcriptions that one can read a draft and simultaneously appreciate the connections between body text, marginalia, previous drafts, later drafts, and earlier and later episodes of the same narrative. Ferrer stressed that the digital editor does still make editorial decisions, for instance, by indicating which marginal text was written first – but the digital editor can offer reading choices (writing order or narrative order?) which a hard copy facsimile or edition cannot.

Other examples of digital resources providing new modes of engagement or even driving research questions were raised throughout the conference: Rachel Nisbet presented on her experience audio-blogging the full text of Finnegan’s Wake, and how the act of reading aloud pushed her into making certain interpretive decisions; her recorded readings are now guiding her close-reading processes for her research.

Digital tools as efficiency tools, extending our ability to do the work we already do – and increasing capacity to do this work from far-flung corners of the globe (or indeed, from bed, although no one admitted to doing digital analysis in their pyjamas) were a recurring feature of the conference. We began the conference with a lecture from Gabriel Egan (De Montfort University Leicester) on early modern print variants, and the exciting process of figuring out where, how and why small changes occurred during a single print run of an early modern text. Here, digital images can reproduce effects which previously required specialised machines – flicking from one .jpg to another to make the changed type ‘move’, for instance.

We also heard from two doctoral students using textual databases for linguistic research – Matthias Heim on ‘peculiar’ words in Shakespeare’s plays, and Richard Zimmerman on grammatical changes in early Middle English. Here, digital resources allow greater breadth, replicability and reliability than manual options. We also saw here some problems related to modelling: the availability of reliable editions in a suitable format, for instance, could very easily determine the scope of a study.

Finally, the weekend ended with a round table for asking questions of and seeking advice from our guest speakers – during which we learned that Gabriel Egan doesn’t like hard copy books, Peter Stokes advised us to get used to task management software, and questions as to whether we have to invest time or academic effort into digital projects were met with the judgement of ‘only if it suits the direction your project is going to take’.

In keeping with the digital mode, Dr Radu Suciu of the University of Fribourg compiled a ‘Storify’ report of the conference tweetstream. Those who wish to recap the conference backwards may do so here. storify.com/radusuciu/cusomedia

Geneva, 5 November, 2011: "PhD Professionalization Workshop" - a report by Arnaud Barras, University of Geneva

The PhD Professionalization workshop took place in Geneva on 5 November 2011. The venue was the bright and spacious building of UniMail. No other building would have been suited to the task of enlightening PhD and MA students about the intricate and sometime obscure process of the doctoral thesis and its outcome. The workshop was a success: around thirty students were present to listen to the three invited speakers, Dr Helen Lawrence and Steve Hutchinson both from Hutchinson Training & Development Ltd, and Sarah Stanton, editor at the Cambridge University Press. The workshop was divided into two distinct parts: with their brilliant communication skills and their experience as former PhD students, Dr Lawrence and Hutchinson discussed the doctoral process, from its genesis to its defense; with her experience as an editor for the prestigious CUP, Sarah Stanton explained how a doctoral dissertation can be turned into a publishable monograph. In the morning, Helen and Steve attempted to make us conscious of the reasons for writing a doctoral thesis. Using all their pedagogical skills, they made us form groups and discuss the various reasons that had led each one of us onto the long and difficult path of the doctorate. One of the ways was to make us choose a postcard among a bunch that was disposed on a table. The image on the postcard was supposed to reflect our attitude towards the PhD. Mine was a close shot of the face of a monkey; the monkey was staring right through the lens of the camera, giving the impression that it was scrutinizing my interiority. It is how I feel about the PhD thesis. To me, it is an exposition of my research, of my thoughts that will take place in a segment of my life that spans about five years. At the end, the thesis will look at me and reveal to me what I have been during this long and tedious, yet thrilling process. For others, the doctorate was a thrilling unknown, represented by a skier jumping. The postcard showed the skier from behind, advancing towards the emptiness of a clear sky. Another postcard represented a doe, but the doe had tusks that looked more like fangs. It is also what the doctoral dissertation can be, a defamiliarizing representation of a seemingly ordinary topic.

Helen and Steve used their communication skills to tell us about time management and the relationship with our supervisor. The gist of the latter being that frequent and regular meetings associated with open honesty with your supervisor will yield the best results. As for time management, efficiency depends on one's way of working: some might work at a slow but regular pace, while others will write a hundred pages in a few weeks. In the end, it is important to know one's way of working so that one will avoid unnecessary panic attacks. The beginning of the afternoon was devoted to the process of orally defending one's dissertation. Helen and Steve gave us some tips as to how to answer certain questions and how to prepare for a detailed criticism of one's work. It was followed by Sarah Stanton's presentation on her work as an editor for the Cambridge University Press. Sarah explained the process of contacting editors and of submitting a project for a monograph. She gave us interesting pieces of advice as to how to write the best proposal to a publisher. The main points were to justify one's project and inscribe it into the literature of the field, to identify very precisely the potential readership and market, to have a title that accurately and shortly describes the content of the book, to describe the scope, content and structure of the book, and also to provide a date for the submission of the final manuscript. The PhD Professionalization workshop was closed by a general yet motivational speech given by Helen and Steve concerning the pros of having a doctorate in our contemporary world. Finally, Emma Depledge played an important part in the success of the workshop. Thanks to her wonderful organization and joyful character, we all learned a lot about the final steps of the doctorate.